I belong in a museum

Last October, I visited Chicago and stopped at the American Writers Museum, a small museum which seems oriented mostly at school groups. It focuses less on artifacts related to writing and more on basic education about the history of American printing and literature... and information about writing craft generally.

They had an exhibit about games writing. I can't overstate how much I disliked it. I've been meaning to blog about that exhibit for months now, and I figured I should finally get around to it.

Part of the reason I put off writing about this exhibit for so long is that it was created with the support of a panel of consultants who are all basically my peers. I really do not know how the materials were created, what it was like working with the museum as a stakeholder, or who actually wrote the text in the exhibits. I got a vibe from the exhibit, but I really can't say how accurately I read it, who introduced it, or why. Furthermore, I have no desire to pile on to creatives who are eager to represent their craft to children - nor to direct any negative attention to the games creators who may have gone out on a limb and agreed to be profiled in the exhibit themselves.

It's important to write about things like this - which peers of mine certainly worked on in good faith - without making a lot of assumptions about what happened and why.

What's more, the degree to which it's worth getting mad at a children's museum exhibit in the first place is pretty debatable. There are far fewer kids out there learning about games writing from this museum than there are learning about it from actual developers on TikTok. If I get a bit tilted about how one single institution in Chicago chooses to represent my field to kids, I can just remind myself: there are more young people out there writing digital and tabletop game content for their own amusement than visit the museum each year. What "negative" impact can a small museum in one city really have on the field?

However, I do think the exhibit says a lot about what games and games writing mean to outsiders. In particular, I think it illustrates precisely what about games writing interests the parents, schools, and other authority figures who have the power to bring kids here. For that reason alone, I think it's worth mentioning on my blog!

I am going to talk about this exhibit as a product of the museum. This museum is clearly an institution with a mission, a character, and financial resources of its own, independent of anyone they choose to work with or represent.

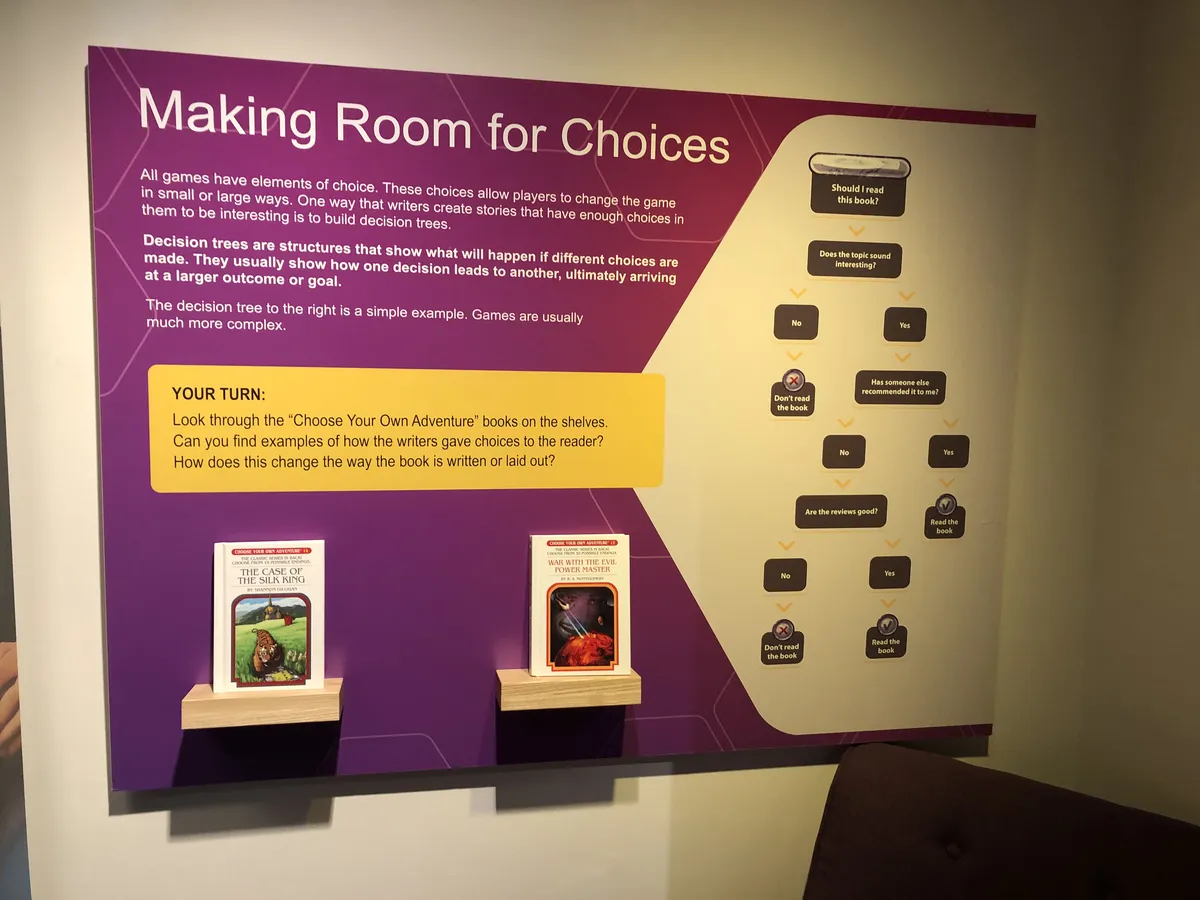

To set the stage: the exhibit was a short hallway with interactive exhibits and writing on each wall. One wall displayed information mostly about the craft of tabletop writing, roleplaying, and LARP, with a single panel about decision trees (illustrated using a pair of CYOA books). It's important to note that Wizards of the Coast is listed as a "partner" of the exhibit.

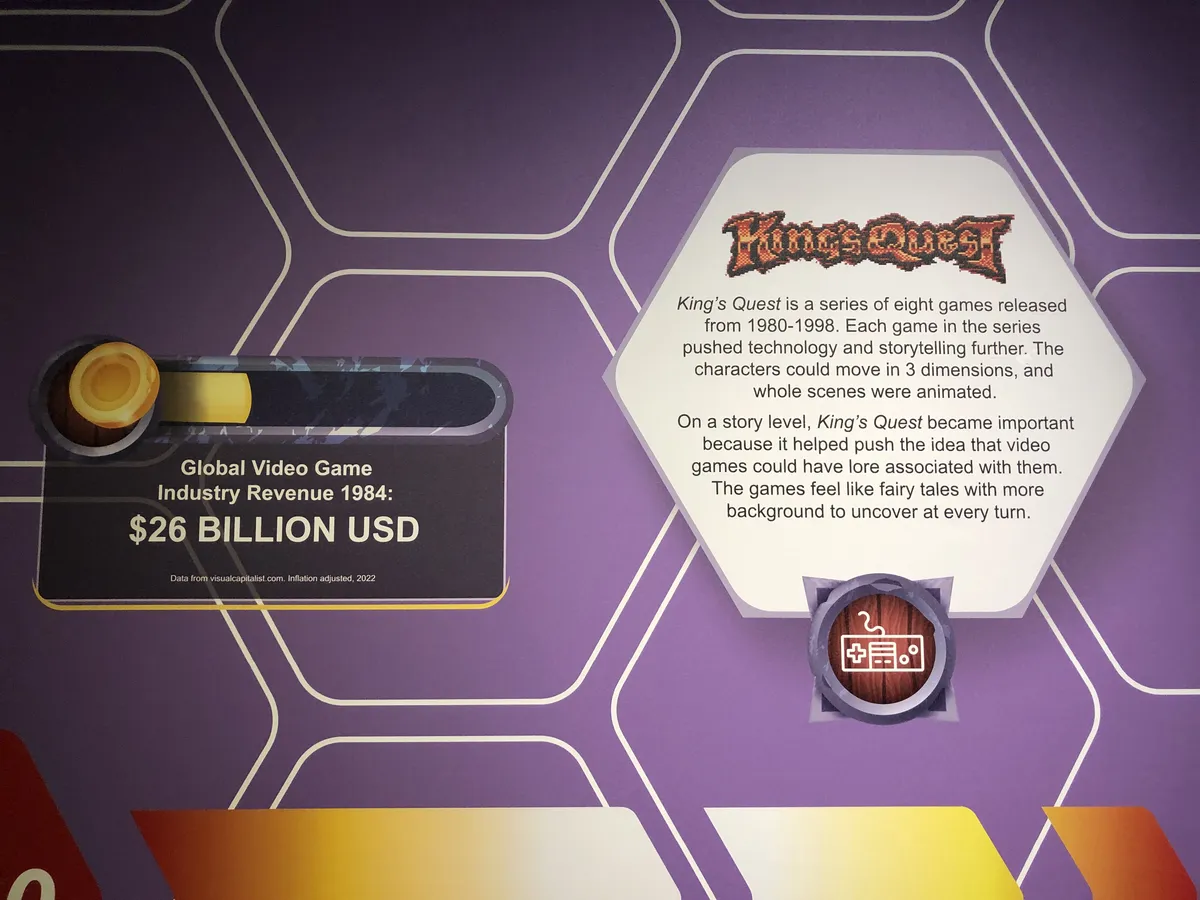

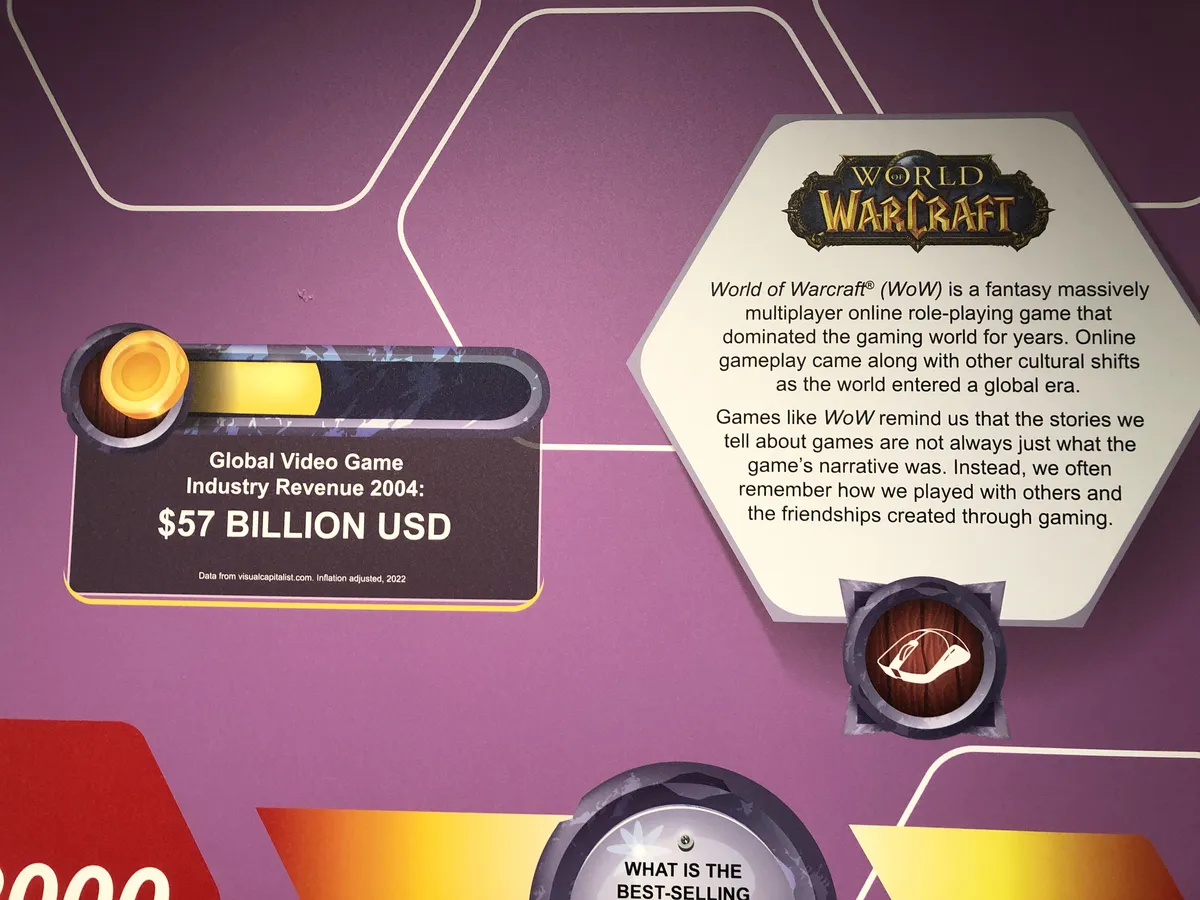

The other wall was a gigantic timeline of the digital and tabletop games industries combined. It has a particular focus on the rising revenue of the games industry and on a canon of popular videogames, many of which are not particularly narrative-focused.

I photographed, I think, every single placard and text element in the entire exhibit. Here are some of my pictures. Can you guess what part of the exhibit design irritated me the most??

Global Video Game Industry Revenue 1984: $26 BILLION USD

King's Quest

King's Quest is a series of eight games released from 1980-1998. Each game in the series pushed technology and storytelling further. The characters could move in three dimensions, and whole scenes were animated.

On a story level, King's Quest became important because it helped push the idea that video games could have lore associated with them. The games feel like fairy tales with more background to uncover at every turn.

Global Video Game Industry Revenue 2005: $57 BILLION USD

World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft (WOW) is a fantasy massively multiplayer online role-playing game that dominated the gaming world for years. Online gameplay came along with other cultural shifts as the world entered a global era.

Games like WOW remind us that the stories we tell about games are not always just what the game's narrative was. Instead, we often remember how we played with others and the friendships created through gaming.

WHAT IS THE BEST-SELLING VIDEO GAME CONSOLE OF ALL TIME GLOBALLY?

Hint: It first debuted in 2000.

THE SONY PLAYSTATION 2

As of 2023, the PS2 has sold more than 158 million units worldwide since its release.

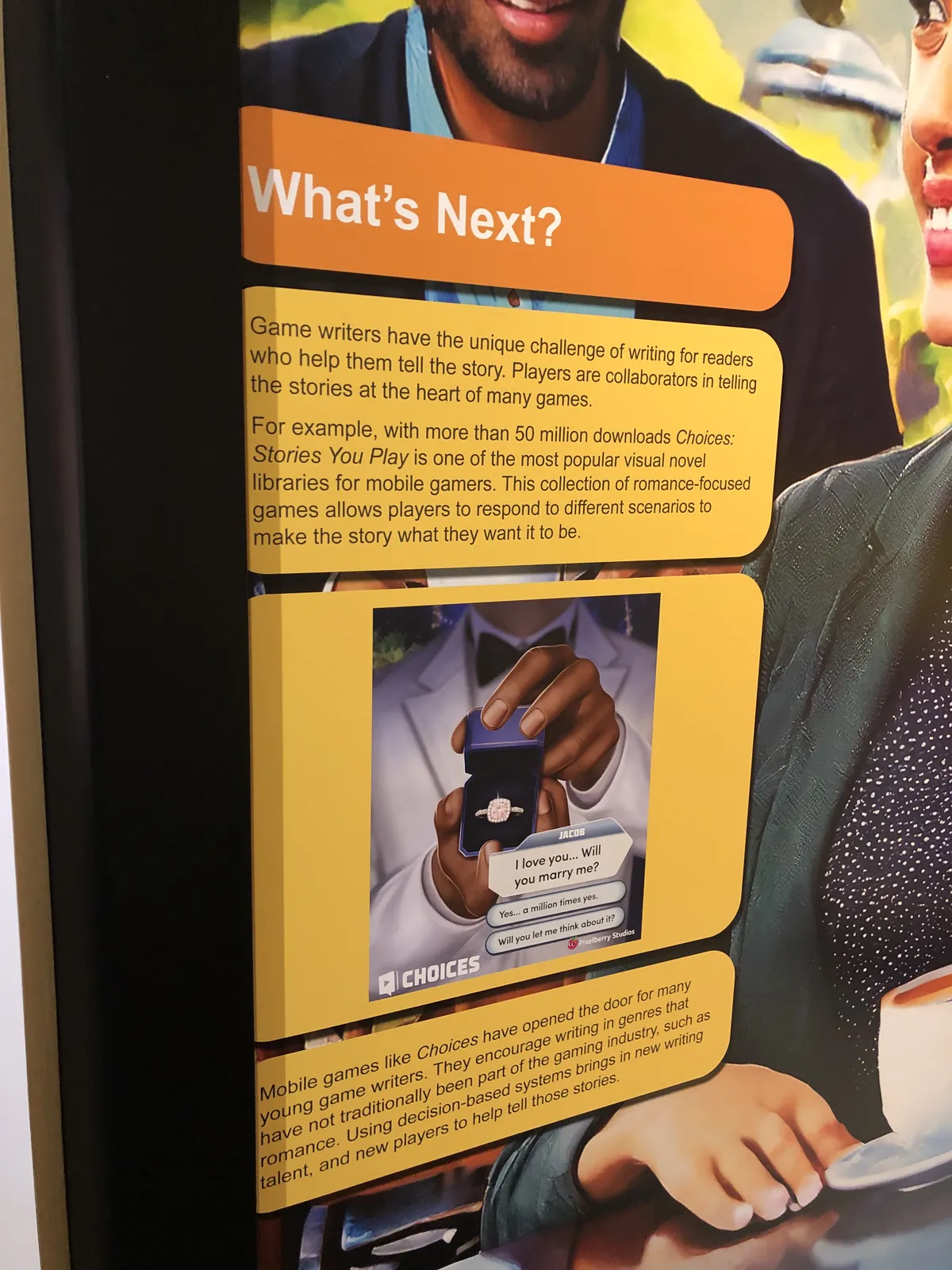

What's Next?

Games writers have the unique challenge of writing for readers who help them tell the story. Players are collaborators in telling the stories at the heart of many games.

[A branded Choices advertisement screenshot showing a man in a suit presenting the viewer with an engagement ring]

[Will you marry me?]

[Yes... a million times yes!]

[Will you let me think about it?]

For example, with more than 50 million downloads Choices: Stories You Play is one of the most popular visual novel libraries for mobile gamers. This collection of romance-focused games allows players to respond to different scenarios to make the story what they want it to be.

Mobile games like Choices have opened the door for many young games writers. They encourage writing in genres that have not traditionally been part of the gaming industry, such as romance. Using decision-based systems brings in new writing talent, and new players to help tell those stories.

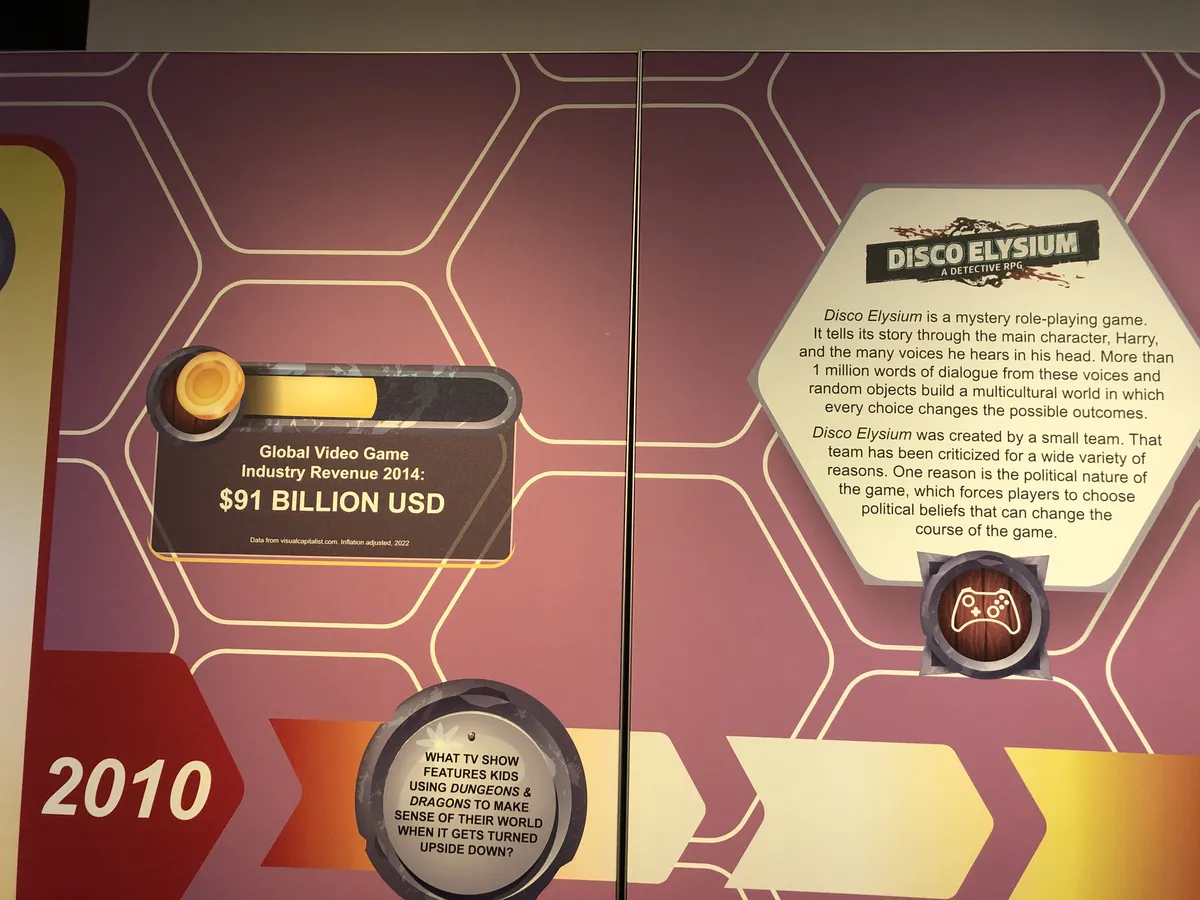

Global Video Game Industry Revenue 2014: $91 BILLION USD

Disco Elysium

Disco Elysium is a mystery role-playing game. It tells its story through the main character, Harry, and the many voices he hears in his head. More than 1 million words of dialogue from these voices and random objects build a multicultural world in which every choice changes the possible outcomes.

Disco Elysium was created by a small team. That team has been criticized for a wide variety of reasons. One reason is the political nature of the game, which forces players to choose political beliefs that can change the course of the game.

The short summary of my anger: much of this exhibit is just a videogame industry finance timeline. It is trying, very hard, to justify games-as-an-art-form via a) revenue, and b) mass-market cultural impact. You can follow the increasing billions of dollars of revenue down the wall from the 70s to the 2020s. As you walk, the exhibit tries very, very hard to boast about the industry's financial power in the same space as it gestures at creators and works which reject and critique capitalist power.

I said I wouldn't guess about the creative process here, but you can really feel multiple hands at work, multiple levels of real experience, and multiple layers of understanding and passion. You can press your ear to the wall of the kitchen and hear that many cooks are present. It's pretty wild!!

Sometimes I look at that photo of the Disco Elysium placard and feel my soul separate from my body!!

The exhibit is trying to prove videogame writing's validity through the vector of, primarily, finance and user counts. But it also fails to really depict digital games writing in any meaningful way whatsoever. The exhibit didn't include any of the things that middle and high schoolers passionate about digital game stories actually want to learn, in my experience.

The most shocking element of the exhibit to me was that I could find so little about what the day-to-day labor of games writing is actually like. There is an interactive writing area focused on brainstorming tabletop characters from a player's perspective, but nothing meaningful about digital games writing. (I do not count the Choices placard.) There were no screenshots of tools, and no discussion of the term "narrative designer". The exhibit did not express how much of the job is interdisciplinary collaboration.

That collaboration is the most surprising and interesting truth about the profession, particularly for kids. The number one thing that kids ask me is: do you get to choose what happens in the game? There is sooooo much space to pick that question apart in a museum exhibit for middle schoolers and high schoolers. You can discuss it in terms students understand - the same language you use to discuss a team project in school. I know this because I have a talk about game dev teams that I sometimes do give to high schoolers!

I think a compelling exhibit about digital games writing for kids would talk about how easy it is to get started, and how huge the possibility space is, particularly when you buddy up and work with a friend, like an artist, who can add an additional kind of storytelling to your writing. The Choices placard is laughable - I don't think it's responsible for a museum to recommend a walled garden visual novel app when Ren'Py is right there. It's a pretty damaging route to send a kid on when most of the tools we adults!!! use are completely free and open.

I think the exhibit should have also actually depicted the tools games writers work with. You don't have to use the terms "string table" or "Unreal blueprints" or "Ink" or "localization" or "VO record," but you should, at the very least, have pictures of these or similar tools and processes in action. You should gesture at the concept of narrative design. And maybe you should have a pamphlet about free tools they can use to get started themselves!

But this exhibit is not talking to kids at all. Instead, the digital games part of this exhibit feels like it is justifying itself to people who have zero personal interest in digital games writing whatsoever - the parents or the institutions which are bringing the kids here. It honestly really pissed me off!

I have sampled only the tiniest slice of how weird this exhibit is. I really have no desire to pick apart any of the individual placards I photographed, but I did spend over an hour reading them and pulling my hair out. I then went back to my hotel room and read them all again. There is also good stuff in the exhibit, but it is bookended by some even more surprising, bad, and weird stuff I haven't even gone over - some takes I just don't have the energy to pick apart in this post.

But here's one more for the road:

"The thing about a computer game character is that a part of you becomes that character in an alterative world. That little gnome [in World of Warcraft] was an emotional projection of myself." - Felicia Day

It doesn't tell kids what they can actually do to write a videogame. Instead, it wastes space calling upon the cultural clout of... Felicia Day, someone their parents haven't thought about in ten years. Amazing. The exhibit is pleading with parents to take games seriously, but it isn't even persuasive.

There are probably dozens of conversations that professionals could have about this exhibit, who it is speaking to, and why. It is such a sharp and distressing example of how authority figures see us and our industry.

Of course, this exhibit is fully downstream from a variety of cultural pressures and preoccupations that I know about, but cannot discuss with any real expertise. In a world where regular people live increasingly precarious lives, where decades of conservative rhetoric have eroded the perceived value of arts education, it makes sense that some arts educators would grasp desperately for any proof that writing can make your kid rich.

During this same trip, I also visited the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry's bicycle exhibit, which also shocked me. I wrote about it here. That exhibit platformed startups and corporations that gave them bikes for free as a form of marketing - including silly, impractical bikes which the exhibit essentially lies about.

Believe it or not, this trip was the first time in my life when I'd been to museums with exhibits about things I knew way the fuck more about than the museum staff did. I had a profound realization that museum exhibits are not all put together with the same goals and resources as the big fucking fancy museums I've visited in NYC many times.

And of course, I was also left wondering: oh my god, how many lies or half-truths have I read in the NYC Met over the years without realizing it??

I love the Museum of Jurassic Technology in LA, so I've experienced that museum's critique of museums many times. What does the act of sticking something in a museum do to the thing? How do the forces which motivate museum staff affect the material? What language is "museumy"? What makes something "look" "truthful" in a museum context? It appealed to me because I did an independent study project in college where I designed an exhibit about the history of laboratory demonstration equipment. My professor had been particularly interested in the processes by which workers like scientists and historians create scientific knowledge and history. I'd taken his class on the history of science, and I'd spent a lot of time standing around with him in a basement full of old artifacts while he talked about these things.

This exhibit about games writing really made me think about that stuff in a much more concrete way than I ever had before. It's one thing to understand, intellectually, that a museum changes the things it depicts. It's another thing to actually see yourself in the funhouse mirror.